#Place de la Bastille

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

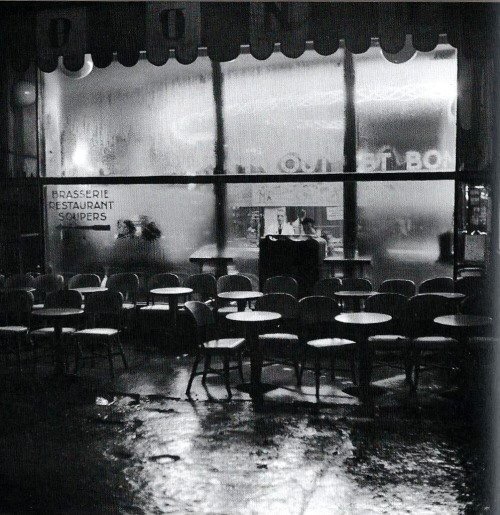

Marcel Bovis - Place de la Bastille Paris 1947

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcel Bovis, Place de La Bastille, Paris, 1947.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photogenic advertisement for the newest ‘conservative’ magazine in France - featuring the daughter of a famed antisemite and an anti-immigrant Parisien (of italian and franco-algerian descent).

Both are anti-immigration, alarmist, and have seen their popularity multiply with the present economic unrest - despite dubious credentials and track records of negligence.

In recent elections of July 2024, leftists and moderates formed a coalition to prevent these extreme-conservatives from obtaining a significant majority in parliament.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

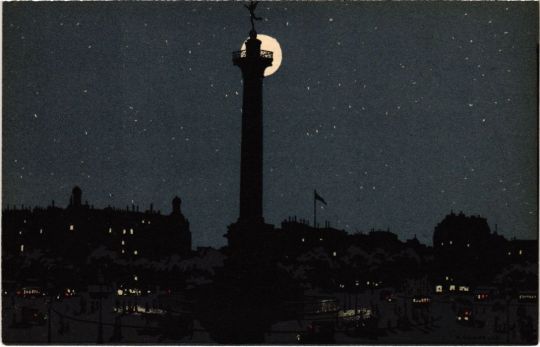

July 1830: the Revolution I forgot

This is Bastille square in Paris. As anyone who's had history classes in France will know, this is Bastille as in Bastille day, 14 July 1789, when Parisians raided the Bastille prison to get weapons for their revolt against the king - the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

It's also rather well known in France that the Bastille prison was demolished shortly after, as Paris rid itself of symbols of the Old Regime. So it would make sense that this monument commemorates that, right? It's super famous, after all.

Wrong. This column commemorates the events of July 1830, some forty years later, the significance of which, I'll admit, I had forgotten.

So here's how it goes. Since 1789, France had oscillated between fragile compromises of constitutional monarchy, revolutionary fanaticism and the iron fist of Napoleon. Following the defeat of 1815, Paris entered a period of calm acceptance under King Louis XVIII, but his successor, Charles X, wanted to go back to the old ways.

So, in July 1830, Paris revolted again. Disposing of the king was a surprisingly quick affair, as in just three days, Charles X was gone. He was replaced by his cousin, Louis Philippe, who seemed more willing to placate the bourgeoisie. A new constitution was drawn up, known as the Monarchie de Juillet, or July Monarchy.

In this context, a monument to the victory of 1830 was commissioned, and this is it: the Colonne de Juillet (July Column), a 47 metre-tall column adorned with the names of the fallen revolutionaries, a mausoleum at the base and the Spirit of Freedom on the top - and is that camera surveilling the street below?

Louis Philippe had ascended to the throne after a revolution, but he would also descend from the throne after the next. In February 1848, Paris revolted for a third time, swiftly ending the July Monarchy and establishing the Second Republic... which, within just 4 years, would become the second Bonaparte dictatorship.

#France#Paris#Bastille#Place de la Bastille#Colonne de Juillet#Monarchie de Juillet#visiting with friends from Japan#and this column stumped me#I had forgotten what had happened in 1830#but the friends from Japan really liked the market!#their first experience of a French marché#2024-06

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

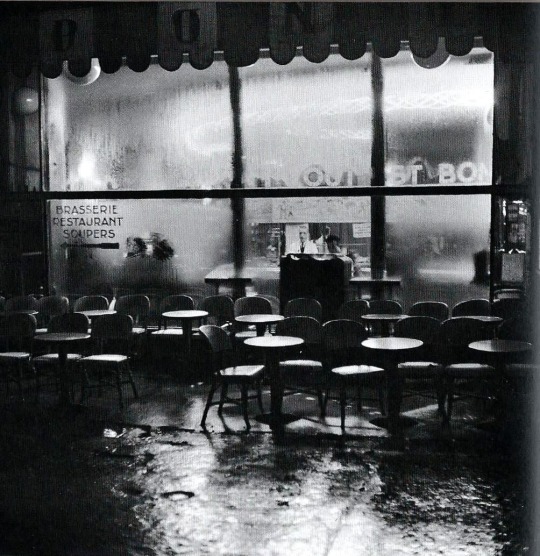

Bernard Buffet (1928-1999) L'Avaleur de Sabres, extrait du recueil Mon Cirque, 1968. - source Heritage Auctions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vous ne le remarquez plus,

Vous ne l’entendez pas.

Mais le gracieux génie de la Bastille,

Entre deux « Ça ira » malicieux,

Vous le répète, inlassable :

Ne jamais baisser les bras,

Et toujours viser la lune.

Car, comme disait Oscar,

On est sûr au moins

De toucher les étoiles.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Place de la Bastille Square by night in Paris

French vintage postcard

#postcard#ansichtskarte#briefkaart#photography#paris#carte postale#vintage#postkarte#square#photo#historic#night#postkaart#place#ephemera#bastille#sepia#tarjeta#french#place de la bastille square#postal

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

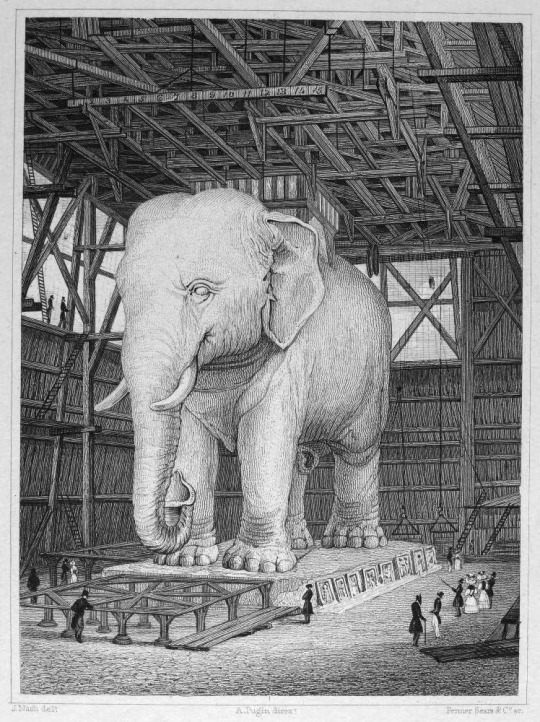

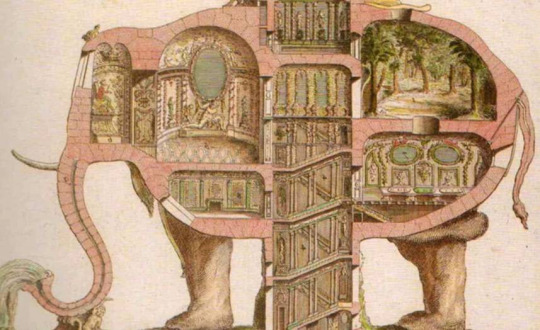

Oh, tomorrow we’ll read the elephant chapter! Many years ago, it served as my introduction to Les Misérables. When I was barely older than the elder of the two young Thénardiers (around eight or nine years old), we had to read it in school. I recall being quite traumatized by it: poor children, and poor cat eaten by rats. The only thing that immensely impressed me was the idea of the elephant in which one could live! And when I revisited the book in a more appropriate age, I was impressed once again – this time, I was moved to tears by this passage: “It seemed as though the miserable old mastodon, invaded by vermin and oblivion, covered with warts, with mould, and ulcers, tottering, worm-eaten, abandoned, condemned, a sort of mendicant colossus, asking alms in vain with a benevolent look in the midst of the crossroads, had taken pity on that other mendicant, the poor pygmy, who roamed without shoes to his feet, without a roof over his head, blowing on his fingers, clad in rags, fed on rejected scraps. That was what the elephant of the Bastille was good for.” I like every description of the elephant in this chapter, but this one is my favourite! And then, while pursuing my PhD, I read "Citizens" by Simon Schama, where the elephant served as the opening symbol in the extensive narrative about the French Revolution. I just feel that this elephant is an important part of my life!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, Olympe de Gouges Was Not Executed for Being a Feminist

As @mathildeaquisexta and @robespapier already explained so well in this post, let’s be clear once and for all: Olympe de Gouges was not executed because she was a feminist, nor for any misogynistic reason.

She was executed under suspicion of modérantisme—a political stance that did not necessarily imply opposition to executions or support for clemency—and more crucially, under accusations of counter-revolutionary activity. In her writings, she advocated either a return to constitutional monarchy or the establishment of a federal republic. Given the intense internal and external civil war at the time, such views were considered dangerously destabilizing. The Montagnards, under mounting pressure, resorted to increasingly harsh measures—something that does not excuse their actions, many of which were indefensible, but places them in a broader revolutionary context.

Some sources—though I’ve yet to locate them again, so this should be taken cautiously—even suggest that she may have called for Robespierre’s death. In any case, she was far from the saintly figure some portray her as.

Did Olympe de Gouges deserve to die? Absolutely not. Was her execution condemnable, especially from a human standpoint? Yes. But from a legal perspective—however flawed the laws may have been—her writings were seen as criminal and therefore her trial was not, strictly speaking, unlawful.

Her feminism itself was full of contradictions. She opposed revolutionary women taking up arms, for instance. An interesting detail: historian Mathilde Larrère pointed out in a video that when de Gouges rewrote Article 12 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen(La Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen) for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (Déclarations des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne), she significantly altered its meaning.

Here is the original Article 12: "The security of the rights of man and citizen requires public military forces: these forces are therefore instituted for the benefit of all, and not for the personal use of those to whom they are entrusted."

Now Olympe's version: "The guarantee of the rights of woman and citizen requires a major utility; this guarantee must be instituted for the advantage of all and for the particular benefit of those to whom it is entrusted."

Where other revolutionary women were requesting weapons—and rightly so, given that they were at war—de Gouges stood firmly against it. At times, I can’t help but wonder if she wasn’t somewhat disconnected from the reality on the ground.

Yes, it's necessary to condemn lynchings, murders, and other excesses of the Revolution. But we must also avoid the "black legend" narrative that demonizes figures like the Montagnards, the CSP of the year II, Hébertistes, or the Enragés, just as we must reject the "golden legend" that romanticizes the Revolution. Much of the Revolution’s progress was driven by violent struggle: the storming of the Bastille, the fall of the Tuileries (which finally removed Louis XVI—a serious threat to the nation and the revolution because of his betrayal), or even the uprisings of enslaved Black people in the colonies.

These were violent acts—but how else could centuries of brutal oppression be overthrown? Enslavers were never going to relinquish power simply because someone asked nicely. The system itself was inventive in its cruelty and designed to resist any path toward Black liberation.

And yet, Olympe de Gouges, despite being an abolitionist, condemned the Haitian revolt in 1792. In a striking and disturbing passage from her play L'Esclavage des Noirs ou l'Heureux Naufrage, she directly addresses the enslaved and says:

"It is to you, now, slaves, men of color, that I am going to speak; I may have undeniable rights to condemn your ferocity: cruel ones, by imitating the tyrants, you justify them. Most of your masters were humane and kind, and in your blind rage, you do not distinguish innocent victims from your persecutors.

Men were not born for chains, and yet you prove they are necessary. If overwhelming force is on your side, why unleash all the furies of your burning lands? Poison, iron, daggers, the invention of the most barbaric and atrocious tortures cost you nothing, they say. What cruelty! What inhumanity! Ah! How deeply you make those groan who sought to prepare, through tempered means, a gentler fate for you — a fate more worthy of envy than all those illusory advantages with which the authors of France’s and America’s calamities have misled you.

Tyranny will follow you, as crime clings to those perverse men. Nothing will ever bring harmony among you. Fear my prediction — you know whether it is founded on true and solid grounds. I speak my oracles based on reason and divine justice. I do not recant: I abhor your tyrants; your cruelties fill me with horror »

Frankly, this is appalling. To suggest that enslaved people—who had endured horrors that defy comprehension—were just as bad as their oppressors is a cruel and absurd false equivalence when we know all the horrors of the slavery system and even if there were deaths on the other side who were truly regrettable, it is clearly not comparable. And what “tyrants” is she referring to? At the time, there was no formal revolutionary government in place in Saint-Domingue. There was no “major force” on their side. At that point in time, slavery had not yet been abolished, and the arrival of Sonthonax — a proponent of the gradual abolition of slavery — marked a turning point. One of the key factors behind the push for abolition was the execution of Louis XVI, which led some white royalist planters to seriously consider turning Saint-Domingue over to the British. In this context, the text appears, in my view, somewhat disconnected from the historical and political realities of the time.

In short, this is a deeply misjudged and insulting passage. That said, she's far from the only historical figure with contradictory views on slavery—Brissot and even Robespierre had their own problematic moments.

To her credit, de Gouges was lucid in other respects. She opposed the war that Brissot advocated, aligning instead—whether consciously or not—with Danton, Robespierre, and Billaud-Varenne, who foresaw the catastrophe it would bring. According to historian Antoine Resche, she supported constitutional monarchy but rejected the property-based voting system (suffrage censitaire).

Still, Olympe de Gouges was not widely known among revolutionary women of her time. Her Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne (Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen) had limited impact. The true revolutionary womens "stars" were Théroigne de Méricourt, Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, Sophie de Grouchy, Louise Reine Audu, Manon Roland, Louise de Kéralio, Simone Evrard, Albertine Marat, the Ferning sisters, Rosalie Jullien, Sophie Momoro (as Goddess of Reason), Jeanne Odo, and perhaps Marguerite David ( of the group of Enragés).

In fact, it’s likely that de Gouges knew of these women, but not necessarily the other way around. Even after her execution, I’ve found almost no evidence of posthumous recognition during the revolutionary period.

From Year III to IV, women like Sylvie Audouin, Thérésia Tallien, Marie-Anne Babeuf, Sophie Lapierre, and possibly Élisabeth Le Bon (widow of Joseph Le Bon) gained more visibility — though Thérésia and Babeuf were probably more famous than Audouin or Lapierre. Still, Olympe remained largely absent from the collective memory ( at least to my knowledge). So she wasn't completely unknown, but her importance wasn't as great as some people would have us believe.

According to Mathilde Larrère, Olympe de Gouges only emerged from oblivion thanks to feminist Benoîte Groult, who revived her memory and her declaration. This was a fantastic move—it's always good to recover lost revolutionary voices.

But ironically, her legacy has since been co-opted by people who hold a very dark view of the French Revolution, some even veering toward counter-revolutionary ideals—because, yes, de Gouges was a staunch monarchist. Even worse, some who now praise her aren’t feminists at all, but use her image dishonestly to discredit the Revolution as a whole.

And the tragic twist? The women who were famous during the Revolution—Louise-Reine Audu, the Ferning sisters, Sophie Momoro, Marguerite David, Jeanne Odo, Rosalie Jullien, Sylvie Audouin, Sophie Lapierre, Marie-Anne Babeuf, Elisabeth Le Bon, Louise de Kéralio—have largely disappeared from collective memory. Others have been demonized or reduced to caricatures: Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, Simone Evrard, Albertine Marat.

Once again, my point is not to demonize Olympe de Gouges, but to highlight the problem of turning her into the only legitimate feminist voice of the French Revolution, while erasing or vilifying all others just because they held different political views.

If people genuinely want to honor Olympe de Gouges, they should portray her in full:

Her strengths—her opposition to property-based voting, her fight for the rights of children born out of wedlock, her courage in speaking out, her revolutionary spirit, her willingness to denounce Louis XVI’s betrayal despite her monarchist leanings.

And her flaws—her rejection of women bearing arms, her naivety about nonviolent change, her harsh and misguided condemnation of enslaved people fighting for their freedom.

She was sincere in her convictions, passionate about justice, and undoubtedly brave. But she was also human, with contradictions and limits like any of us.

One day, I hope to see a real film that portrays all the women of the French Revolution—regardless of their political alignment—without distortion or demonization.

#frev#french revolution#olympe de gouges#feminism#women's rights#women in history#sexism#slavery#revolution

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Opera House - Paris - 1900 & 2000

The Palais Garnier also known as L'Opéra Garnier is a historic 1,979-seat opera house at the Place de l'Opéra in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was built for the Paris Opera from 1861 to 1875 at the behest of Emperor Napoleon III. Initially referred to as le nouvel Opéra de Paris (the new Paris Opera), it soon became known as the Palais Garnier, "in acknowledgment of its extraordinary opulence" and the architect Charles Garnier's plans and designs, which are representative of the Napoleon III style. It was the primary theatre of the Paris Opera and its associated Paris Opera Ballet until 1989, when a new opera house, the Opéra Bastille, opened at the Place de la Bastille. The company now uses the Palais Garnier mainly for ballet. The theatre has been a monument historique of France since 1923.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

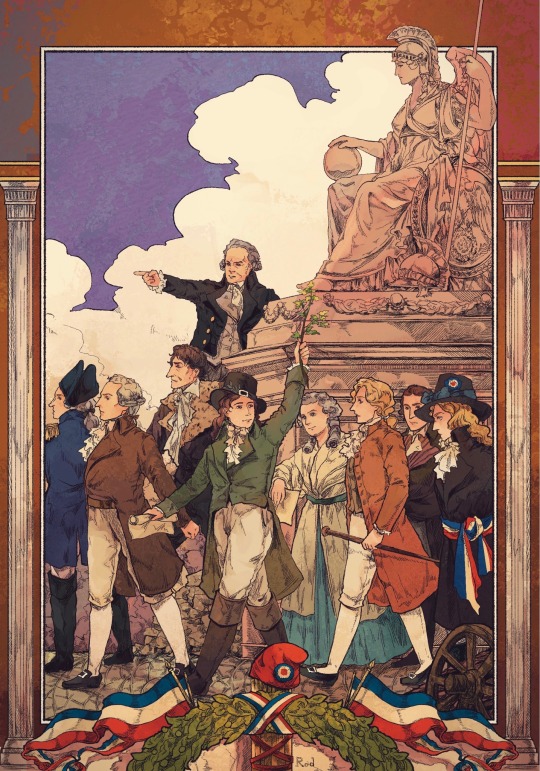

A la Bastille!!【2/6】

I put Camille Desmoulins in the centre because I seriously love this guy

The others are: Lafayette ( I know he doesn’t actually belong but he deserves a place), Danton, Marat, Robespierre, Olympe de Gouges, Francis, Brissot and Saint Just

896 notes

·

View notes

Text

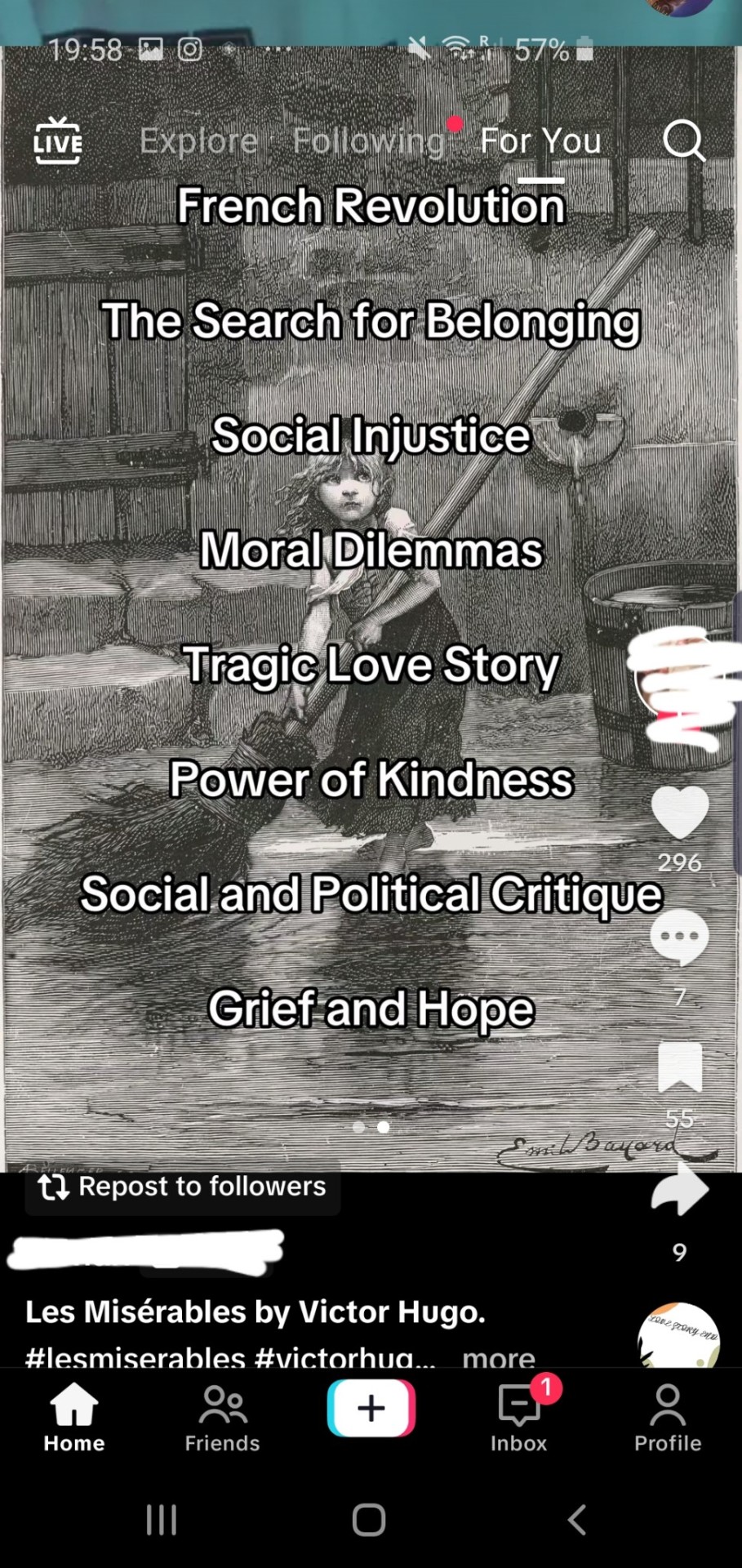

THE JUNE REBELLION: NOT THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

i fear we need to talk about this since i've seen so many tiktok referring to the french revolution when talking about les miserables and it needs to be addressed (aka i'm going to get it out of my system once and for all so i can stop being bitter about it)

i mean, i see those kind of tiktok too much and i am annoyed so bare with me:

so, let's start with les miserables: when does it takes place ?

the chronology of les mis is very long, but the part everyone is referring to (and everyone's favourite part) is the barricades. the barricades takes place during the June Rebellion.

now what is the June Rebellion?

it's a two days rebellion that arise in Paris in an era of political and social instability.

in 1832. 43 years after the french revolution.

so it's safe to say, the plot of les miserables is not at all taking place during the french revolution. and this rebellion was a failure (a flop, as some might even say) and did not overthrow the government (sadly) at all for various reasons.

(see this post here about it, even thought pinpointing the reasons to why a revolution fails is, imo, a bit hard and i am in no way shape or form an historian)

now, for the French Revolution.

keeping it very simple, it starts in may 1789 and end on november 9th 1799 when napoleon did a coup and took the power (others (marxists mostly) might argue that it ended with the death of robespierre, soooo pick your poison). so right of the bat: the french revolution is not one big battle and boom, it's a long period of changes and instability.

i think what people refer to when saying "the french revolution" might be the 14th of July, with the Prise de la Bastille. i know it's a very important event as it is our national day (yay liberty) and it's historically the first big intervention by the parisians (as in the people as in the poor) in the revolution. personally i'm not crazy about this moment (i really really like the march of the women to Versailles in october 1789, insane) it wasn't actually that big of a battle but the repercussions were huge so good job. but here is the problem then, what would make you think this successful battle is the battle we see in les miserables?

[i'm gonna go on a personal mini-rant here but it seriously worries me that so many people, mostly Americans, have so little knowledge of this. i'm not saying you should know everything about french history (as a matter of fact you should not why would you do that to yourself) but it's like... basic knowledge. and what worries me the most is that they think a failed two days rebellion is the french revolution as if it was not an event that reshaped the entirety of the french political system and was a trigger to a lot of changes in europe???? i mean... look at that: ]

i know we have a lot of revolutions in french history but if you need to know one, know the French Revolution, at least just the fact that it was a years long event with successful battles and a successful outcome (not gonna go into the whole it's a revolution for the bourgeoisie thing even if... well it kinda is).

and if you have not read/seen les miserables with your eyes closed, you know that it is very not successful at all !

anyway, that's it !

to summarise:

French Revolution = 1789 / very long / successful outcome / successful battles / not in Les Miserables

June Rebellion = 1832 / 43 years after / two days long / failure / in Les Miserables

Recommendations of...

Movies during the French Revolution = Danton (Andrzej Wajda) / La Revolution Française I and II (Robert Enrico & Richard T. Heffron)

Musicals during the French Revolution = La Revolution Française (Alain Boublil & Claude-Michel Schoenberg, yes same dudes that made les mis the musical) / Les Amants de la Bastille (not good but definitely super fun to watch) / The Scarlet Pimpernel (Nan Knighton, haven't seen it but some of the songs SLAPS)

Now you can obsess on the french revolution correctly ! and it's all very good recommendations too ! yes !!!!!!

(some of my fav les miserables adaptations here too)

i'm done, thanks for sticking with me, i love you all and i will stop yapping now ! buh-bye!

#i promise i will stop be bitter about that now that it's out of my system#my french heart could not take it anymore im sorry#les mis#les miserables#victor hugo#the brick#june rebellion#the french revolution#french history

25 notes

·

View notes

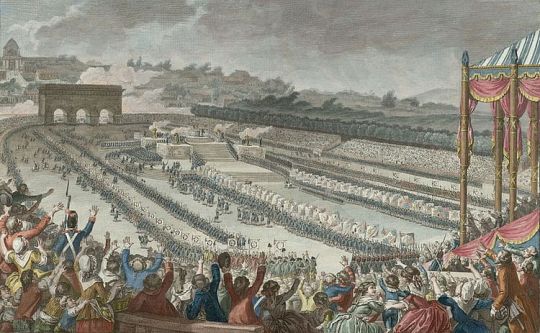

Photo

Festival of the Federation

The Festival of the Federation (Fête de la Fédération) was a celebration that occurred on the Champ de Mars outside Paris on 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille. With over 300,000 people in attendance, the event honored the achievements of the French Revolution (1789-99) and the unity of the French people.

The festival itself was a monumental accomplishment, as tens of thousands of French citizens volunteered to labor in the mud and rain to build an amphitheater on the Champ de Mars with a colossal Altar of the Fatherland at its center. The event marked the birth of French patriotism, at least in the sense that such a term is understood today, and was the first celebration of 14 July, France's national holiday, which is still annually celebrated. At the same time, the festival was perhaps the high watermark of unity during the French Revolution itself, since afterward the revolutionaries devolved into factionalism and politics based on terror.

Unifying a Nation

By 1790, France was a nation intoxicated with revolutionary fervor, just as the French had begun to discover their national fraternity. The National Assembly, the representative body that had risen in defiance of the king during the Estates-General of 1789, had already declared the abolition of feudalism and noble tax privileges in the August Decrees and had proclaimed the natural rights of men in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. It was a new day in France, one in which all citizens could stand beside their neighbors as equals, at least in theory if not quite in practice. The feasts of the federations that sprang up across the country and culminated in the ecstatic, massive festival on the Champ de Mars celebrated not only the Revolution but also this sense of unity that had not existed in France under the Ancien Régime.

Prior to the Revolution, Ancien Régime France was a collection of regions that differed from one another in their customs, languages, and sets of laws. Partially owing to their origins as feudal domains that had little in common besides fealty to the same king, some French territories still valued their own local identities above that of the collective nation. Scholar William Doyle uses the example of Brittany where, even on the eve of the Revolution, people were more likely to speak Breton than French and dressed in traditional garments. In some areas, especially in the north, laws were customary, with over 300 local customs being observed. This differed from the south, which largely followed Roman law. As Doyle points out, this could lead to much confusion, as "the law relating to marriage, inheritance, and tenure of property could differ in important respects from one district to another; and those who held property in several might hold it on widely differing terms" (4). Even royal edicts could be contested by certain local parlements, the high judicial courts, which could refuse to register them within their jurisdictions. Other barriers to unity under the Ancien Régime included poor infrastructure outside metropolitan areas like Paris, hindering the flow of information, as well as taxation which also varied from place to place; the whole French landscape was pockmarked with internal customs barriers, set at multiple different rates on a wide range of items. Even currency and units of measurement differed, enough to make any foreign traveler mad with frustration.

But aside from merely upsetting 18th-century tourists, these differences frustrated any kind of national cohesiveness. Historical grievances and feuds between provinces worsened the issue. To some, unity of any kind seemed impossible; to emulate these feelings, French historian Jules Michelet writes:

How will Languedoc ever consent to cease to be Languedoc, an interior empire governed by its own laws? How will ancient Toulouse descend from her capital, her royalty in the south? And do you believe that Brittany will ever give way to France?...you will sooner see the rocks of Saint-Malo and Penmarch change their nature and become soft. (441)

Yet, the Revolution had done the impossible and given hope to France's 27 million people. By spring 1790, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) had reluctantly consented to the Revolution's radical reforms and was living as a virtual prisoner in Paris. Down the street from him, the Assembly was working to codify their progress in a new constitution. And all across the country, common people had joined in the Revolution, as exemplified in the Great Fear of July 1789, when countryside peasants stormed the châteaux of their seigneurial lords. By 1790, many in France believed the Revolution to be over and looked to one another with a new sense of fraternity, united in their devotion to the patrie (fatherland).

This unity manifested itself in the form of liberty trees, which sprouted on village greens throughout France. These trees, trimmed of their leaves and branches, were decorated with ribbons of blue, white, and red, the colors of the Revolution and of the patrie. As trees had long symbolized fertility and rebirth, so too had these villages been reborn from the oppression of the Ancien Régime. They were a way for a village to show solidarity with the Revolution, and to tell the world that it "was no longer seigneurial property, and its people no longer dependents" (Schama, 492). Across France, public officials would be sworn in beneath liberty trees, priests would bless them, and joyful citizens would dance around them with hands clasped, entirely devoted to the nation. To paraphrase French socialist historian Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), French liberty, which previously had rested solely with the fortunes of the National Assembly, was now being concentrated in as many centers as there were communes (Furet, 65). Yet the federation movement that would soon sweep France would not be spearheaded by the Assembly or the villages, but by detachments of the National Guard.

Continue reading...

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonjour ☕️ 🥐 🍒, bon Dimanche de Fête Nationale 🇨🇵

Fête du 14 Juillet place de la Bastille 🗼Paris 1960

Photo de Sanford H. Roth

#photooftheday#black and white#photography#vintage#sanford roth#paris#bal du 14 juillet#bastille#bonjour#bon dimanche#14 juillet#fidjie fidjie#bastille day

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

Camille had his speech leading to the siege of the Bastille, Robespierre was in the estates general and a founder of the Jacobin Club and Marat had his newpaper.

I’m not entirely sure when/why Danton became so popular and influential?

TLDR: Danton gained his first notoriety through his position as president at the Cordelier district.

In Dévinir révolutionnaire dans Paris (2016) Haïm Burstin underlines that, indeed, ”Danton did not participate in the political campaign linked to the convening of the Estates General, nor in the drafting of the cahier of the third estate of his district, nor even in the first insurrectional exploits.” In Danton(1978) Norman Hampson similarily concludes that ”the record of [Danton’s] political activities in the first half of 1789 is a surprising blank.” In July 1789, things do however get going slightly. Both Burstin and Hampson cite the lawyer Christophe Lavaux who in his memoirs (1816) claimed to have seen Danton in the Cordelier District on July 13, basically being Desmoulins 2.0:

I saw my colleague, Danton, whom I had always known as a man of sound judgement, gentle character, modest and silent. What was my surprise at seeing him up on a table, declaiming wildly, calling the citizens to arms to repel 15,000 brigands gathered at Montmartre and an army of 30,000 poised to sack Paris and slaughter its inhabitants. Exhausted with fatigue, Danton calmed down and gave way to another fanatic I went up to him and asked what all the uproar was about; I spoke to him of the calm and security I had seen at Versailles. He replied that I had not understood anything, that the sovereign people had risen against despotism. ”Join us,” he said. “The throne is overturned and your old position is lost. Don’t forget that.”

Then in the night between July 15 and 16, two days after the storming of the Bastille, Danton famously led a company of National Guards from the Cordeliers to the Bastille, kidnapping Soulès, the new governor appointed by the Paris Commune, after he refused to let them in and taking him to the Cordeliers and the Hôtel de Ville where he was ordered released by Lafayette the following morning. Danton’s move was openly dismissed and disapproved of by the authorities but we might imagiene it still bought him some notority.

After this, Danton laid his focus on the Cordelier district of which he is elected president in September 1789, a post he kept up until January 1790. On December 11 1789 we find evidence of the notority he’s gained through this, as we on that day see the district offering a ”solemn testimonial to its beloved president in reply to those who dared to imagiene that he was touting for votes to prolong his presidency and had purchased the unanimous support of the district.” (cited in Hampson, page 36). The documentation of what exactly Danton said and did during this period is however still quite lacking. In his memoirs (1875), Antoine-Clair Thibaudeau claimed to in the evening of October 3 1789 have gone to the Cordelier district and seen Danton presiding ”with the decisiveness, agility and authority of a man who knows his power. He drove the assembly of the District towards his goal. It adopted a manifesto.” The manifesto in question was a fierce denunciation of the king’s decision to summon the Flanders Regiment to protect him at Versailles. In number 47 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant, Desmoulins claimed that Danton on the very same day ”sounded the tocsin at the Cordeliers. On Sunday (October 4) this immortal district posted its manifesto, and from that day on, formed the vanguard of the Parisian army, and would have marched to Versailles, if Mr. Crevecœur, its commander, had not slowed down this martial ardor.” (According to Hampson, the authors behind Révolutions de Paris wrote the same thing, but I can’t find the place he’s referring to).

After this, the Cordeliers concentrayed their fire on the municipal government in Paris, in particular Bailly and La Fayette. On December 26 1789 Danton led a deputation from the Cordeliers to the Commune to denounce Bailly for awarding commissions in the National Guard on his own authority and to allege that the commissions referred to Bailly as Monseigneur (My Lord) in letters. When Bailly showed him that these letters did in fact refer to him as Monsieur, Danton did however profess that he’d made a mistake. Then on January 22 and January 23 1790 he openly takes Marat under protection at the Cordeliers after La Fayette the same day had sent an army of 3000 men to arrest him, giving Marat time to escape. On March 17 an arrest warrant was issued against Danton himself for inciting the district to protect Marat in defiance of the law. In response, the next day 300 Cordeliers signed a petition on Danton’s behalf. The business was referred to the National Assembly that, in Hampson’s words, ”was at least becoming familiar with Danton’s name” and it ended up ruling in his favour.

Unfortunately for Danton, in May 1790 the districts were abolished and Paris divided into 48 sections instead, of which only active citizens could be apart of. The Cordelier district now reinvented itself as the Cordelier club, but it lacked any of the concreate political power the Cordelier district had had. As for Danton, according to L’école révolutionnaire des Cordeliers (2016) by Raymonde Monnier, ”if he has friends in Cordeliers and if they count him as one of their own, as Mathiez writes, his action at the club escapes examination.” Danton instead focused on trying to win municipal power, running for both mayor and procureur in 1790. In both instances be did however face massive losses. In September 1790 his section did however choose him as one of three representatives to serve on the new municipal council. All representatives did need to be endorsed by the sections as a whole, and there, Danton was the only one of 144 councillors to be rejected, by no less than 43 of 48 sections. Hampson writes the following about this, cementing that Danton at this point was somewhat famous:

This certainly indicated that he had acquired a Parisian reputation, but not one that looked like doing him any good. The election results showed that there was something special about Danton.

#georges danton#camille: ”table standing is supposed to be MY THING danton!!!”#danton: ”well you stole the whole ”ugly as sin” from me so fair is fair”#frev#ask#french revolution

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

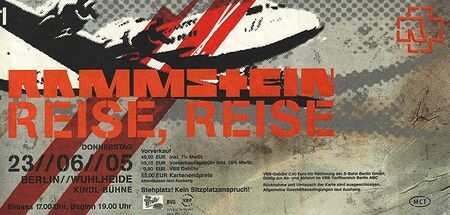

'Rosenrot' turns 19 years old today 🎶💿

On the 28th of October, 2005, the fifth studio album 'Rosenrot' was released, about a year after 'Reise Reise'. The band worked with their usual producer Jacob Hellner in the El Cortijo Studio in Spain as well as in the Teldex Studio in Germany on this album, yet it has to be mentioned that the recording process for 'Rosenrot' was significantly shorter than usual and according to Till, the band felt kind of rushed. Seven songs were already recorded during the sessions for 'Reise Reise' and were left in their original form: Rosenrot, Wo bist du, Mann gegen Mann, Zerstören, Ein Lied, Feuer und Wasser and Hilf mir. New songs for this album developed out of already existing demos, and thus Benzin, Spring, Stirb nicht vor mir and Te quiero puta! were born and added to the list.

To the press, this album was announced under the title 'Reise Reise II'/'Reise Reise (Vol. 2)' in a posting on the official Rammstein website on the 24th of June 2005: Good news: Rammstein are already working on a musical successor, which is expected to be called "Reise, Reise ( Vol.2)". The management explained as follows: "After the production phase of the last album, there were many songs that had not found a place on 'Reise, Reise' at the time for dramaturgical reasons, but could now be finalised. It's nothing unusual . Just as 'Ohne Dich' came from the production time for the album 'Mutter', numerous songs have been waiting for more than a year to be perfected and are now to see the light of day. It's up to the band alone to decide which ones to release."

On the 17th of August 2005, the band decided on naming the album 'Rosenrot' instead and a day later, on the 18th of August, this was officially announced. The first song which was presented to the public was 'Benzin', which was performed by the band at a concert at the Wulheide, Berlin, on the 23rd of June, 2005.

To present the full album to world of music journalism, the band held an event in Paris to showcase the album through a sightseeing tour. Journalists were given a discman with the album and headphones during a bus tour through the city, covering the route from Place de la Bastille to the Seine riverside, where they could board a ship and interview the band members about the album.

Here's an interview with Olli and Paul in Paris. Olli talks for example about how 'Rosenrot' is a calmer record than 'Reise Reise' and Paul mentions how much sex and sexuality plays a major role in their music and in music in general:

youtube

Eight days before the official release of the album, listening samples (about one minute each) of six songs from the album were released online as part of the promotion for the album. These listening samples were also released as a CD.

The album debuted at number 1 on the German album charts in its first week and stayed in the Top 100 for a total of 41 weeks. Over 200,000 copies were shipped, reaching platinum status in the first week. It also achieved platinum status in Switzerland and gold in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, and Finland. 'Rosenrot' reached number 23 in the "Top 50 Albums" chart of 2005.

As a cover, the band reused the Japanese cover of the 'Reise Reise' album. It depicts the US wind-class icebreaker (USS Atka) during an expedition under the leadership of commander Buster E. Toon; the picture was taken on 13 March 1960 at McMurdo Station, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, after it arrived there in a howling blizzard one day earlier. The print on the CD as well as on the DVD (with live perfomances of 'Reise Reise', 'Mein Teil' and 'Sonne') is designed to look like a hatchway of a ship.

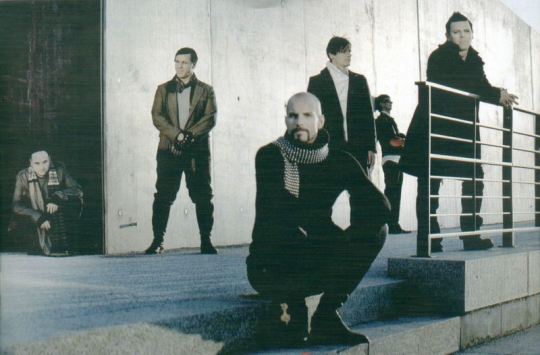

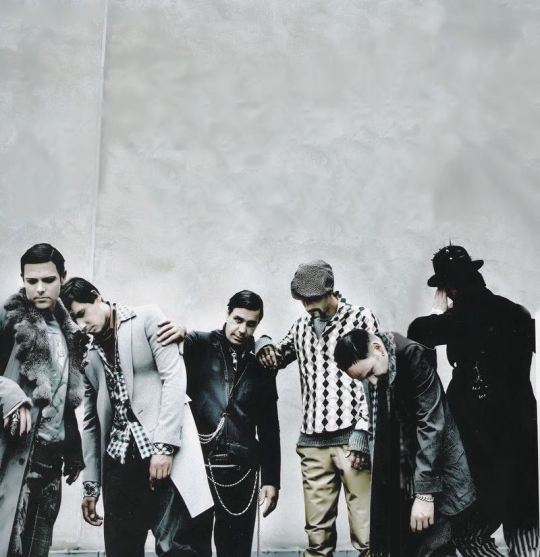

The promotional pictures were taken by Mat Hennek. Flake had fallen ill with Mumps, which already prevented him from attending the Paris promotion, and as a result, he was also unable to participate in the photo shoot. He was replaced by his brother, which is why "Flake" (his brother) is always turning his face away from the camera or why it's hidden behind sunglasses or in the shadows.

Some more little facts about the album and quotes from promotional interviews:

Paul on the song 'Zerstören': We are basically holding up a mirror. The lyrics we written during the war in Iraq. We were interested in the parallels between a marauding pack of kids after a game of soccer who roam the street and destroy everything, and states which invade other states and destroy everything there. Our main thought was that there is no difference. We perceived it as boldness, that the Americans simply bomb a country and get away with it. At the moment George W. Bush is nothing else but another disgusting hooligan.

Olli on 'Mann gegen Mann': We don’t want to discriminate against gays. The song is more for gays. We simply wanted to take the weight off the topic and make it more natural.

as well as on the album name and cover: Actually, the album should be called 'Reise, Reise Vol. 2’. We quickly forgot about that title. Since we see the new album as an independent one, we needed a new title. That was a bit unfortunate, since the cover was already finished. So the ship on the cover picture is now called 'Rosenrot’ and everyone can think about what it stands for. Opposites? The cold world? Where has the love gone? No idea. But the ship does not symbolize the now and us as a band.

Till on the idea behind 'Benzin': One day, I actually watched a movie called Love Liza. It’s the story of a guy who loses his wife and his job and gradually becomes addicted to gasoline. He goes to gas stations and smells the pump. It’s a sort of tragicomedy. Many films have been made about addicts, but never about gasoline sniffers. I think that was the starting point for this song.

Olli on recording the album in Berlin: It’s the first time we’ve recorded in Berlin, at home, and I’m not sure, looking back, that it was a good idea. Our families living nearby, we might tend to look at our watches whenever we had a break : What am I doing ? Do I take the opportunity to drop by home ? As a result, we were necessarily less focused and it was almost impossible for us to be there 100%.

Schneider on 'Rosenrot' as the end of an era: For me, this is the closing of a chapter for the band. Everybody needs a break, they need a bit of distance from this band and time to look forward and ask, ‘Where am I?’ And, ‘What do I want to do?’ We need to find other ways of being inspired.

additional sources: rammwiki, Rammstein history, affenknecht.com, navy.mil

#rammstein#rosenrot album#happy birthday rosenrot!#an album i've grown very fond of over the last year#so happy i could finally quote Olli a lot here#oliver riedel#till lindemann#paul landers#christoph schneider#flake lorenz#richard kruspe#research & rammsplaining#interviews & quotes

43 notes

·

View notes